For Adolf Hitler, German victories in western Europe in 1940 CE were not the real goal of Germany's war efforts.

He envisioned "lebensraum", living space, for the Germans in the east and wanted to exterminate bolshevism and judaism along the way.

Germany had signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with the USSR in 1939 CE, but Hitler was intent on breaking it.

He was wary of growing Soviet strength and wanted to attack before the USSR grew too strong.

Already during the Battle of Britain he ordered his staff to draw up plans for the invasion of the USSR.

These were finalized in the spring of the next year.

The attack was delayed by Operation Marita, which secured the Balkans, and problems with supply.

The importance of this delay for the outcome of the operation is still debated.

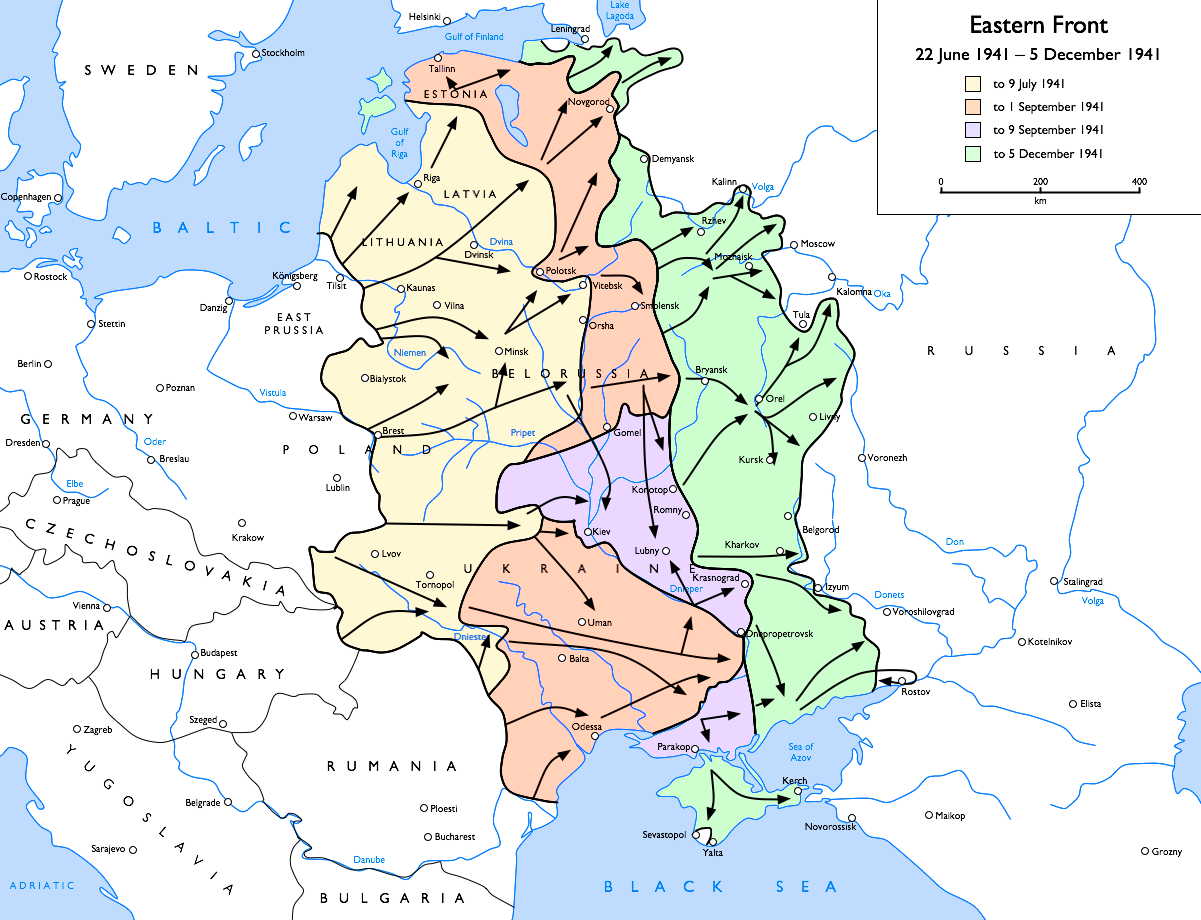

On 22 June the German army was ready and Barbarossa was launched.

Stalin too was preparing for war and may have been readying for an attack himself.

However he did not expect Hitler to strike so soon, while Germany was still locking horns with Britain.

He ignored reports of German troop concentrations and kept the bulk of his forces behind the Stalin line.

There was some reason for confidence, as the Red Army in the west numbered 2.8 million men, 11,000 tanks and around 8,000 aircraft.

But its equipment was outdated and in ill repair; ammunition was scarce; the men were underpaid and in the previous years Stalin had purged the most competent half the officer corps.

Facing them was a German force of 3.8 million men, 150,000 trucks, 650,000 horses, almost 3,500 tanks, 2,800 aircraft and 7,200 artillery guns.

They were split into three armies, each with its own objective:

Army Group North targeted Leningrad; Center advanced upon Moscow and South drove into the Ukraine.

The total front was 1,000 kilometers wide.

The Luftwaffe destroyed 1,500 Soviet aircraft on the first day and another 1,600 in the two following days, quickly achieving air superiority.

On the ground the German army broke through rapidly, using its favorite 'Blitzkrieg' tactics to the full.

In some cases tank units raced forward at a pace of 80 kilometers per day, pausing only to resupply and have the infantry, which could march only 30 kilometers per day, catch up.

In total during the campaign they encircled, defeated and captured some 2½ million enemy soldiers, 10,000 tanks and 16,000 guns.

The Red Army launched some counteroffensives, but these were ill-coordinated and easily repulsed.

The Germans treated both civilians and captured soldiers with contempt.

In the wake of the regular army came Waffen-SS and Einsatzgruppen, who immediately set out on a campaign of extermination to make room for German colonists.

Anybody who was suspected of being a saboteur, partizan, Jew or political commissar was simply killed; common soldiers and non-combatants nearly starved.

The regular German army, indoctrinated with nazi ideology, also participated in this.

The killings did not break Soviet resolve, but hardened it, as it was soon clear to them that Hitler's policies were at least as brutal as those of Stalin.

On the battlefield, despite its early successes, the German army started to encounter difficulties.

The swamps, forests and primitive roads of Russia severely hampered rapid movement.

Supply lines became ever more stretched; the shortage of trucks started to make itself felt;

wear and tear started taking their toll on both troops and equipment.

The Red Army mobilized millions of reserves and resistance gradually stiffened, though its counterattacks kept failing.

Stalin ordered the retreating forces to apply the age-old scorched earth tactic.

The majority of German generals considered Moscow the most important target of the campaign, yet Hitler disagreed.

He temporarily diverted part of Army Group Center south to strengthen the attack on Kiev, though this delayed the advance on Moscow.

Army Group North reached Leningrad in early September, but by then lacked the strength to assault it.

Instead, Hitler ordered the city to be besieged.

This siege lasted well beyond Operation Barbarossa, until January 1944 CE.

In the south Kiev was taken in a month-long battle, where the Germans trapped nearly half a million Soviet soldiers in one of their encirclements.

This made the Red Army temporarily lose its numerical advantage over the Wehrmacht.

In the center Smolensk had been captured in August, but the diversion of the tank divisions southward delayed the final advance to Moscow to 2 October.

After initial success it got stuck in mud, caused by the "rasputitsa", the Russian autumn rains.

While the Germans ploughed on, Moscow was reinforced by general Zhukov and 30 divisions of Siberian troops.

Contrary to the Germans, these were well equipped for what came next: the cold Russian winter that disabled both men and equipment.

The eastern troops rebuffed the attack, counterattacked on 5 December and pushed the frontline back 300 kilometers.

Operation Barbarossa cost the Wehrmacht 800,000 men, 30,000 trucks, 2,400 tanks and 2,800 aircraft.

The Red Army was hit much harder, with 4½ million men killed, wounded or missing and 3½ million taken prisoner, 20,000 tanks and 21,000 aircraft lost.

The offensive came close to achieve its goals, but not close enough.

By setting as many as three targets, the Germans achieved none.

The winter of 1941 CE - 1942 CE was mostly a stalemate.

The Wehrmacht resumed its offensive in the spring, though by then the Red Army had strengthened sufficiently to prevent a decisive breakthrough.

By 1943 CE the USSR, by using its remaining industrial power and adopting German tactics for itself,

turned the tide and two years later fought itself to Hitler's doorstep, proving that Operation Barbarossa was his worst idea.

War Matrix - Operation Barbarossa

World Wars 1914 CE - 1945 CE, Wars and campaigns